Readers, recently an acquaintance – who has been following the crypto scene for some time but has not yet dipped their toes in – asked me about Central Bank Digital Currencies (among other things).

I ended up writing a somewhat broad sweep of the state of Central Bank Digital Currencies.

I think you might find this an interesting weekend read.

Since the first major regulatory interventions into the cryptocurrency space around 2016–17, governments have talked about central bank digital currencies.

India’s central bank, the RBI, has since 2018 hinted about a digital rupee. In July, it even said it planned a phased rollout – although once again without any timeline.

The European Union has been more detailed about its approach to a possible digital euro. Later this year, it plans to start a two year investigation into the design, organisation and rollout. It has explicitly stated it won’t be a ‘crypto asset’, that the ECB will be the custodian of any such currency, and that it will complement cash.

China has had the most broad rollout of any central bank digital currency anywhere. It has run pilots across cities from 2020, and recent examples have shown that it is, in some ways at least, programmable in that specific e-yuan tokens can be used for specific purposes.

Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, has talked previously about a global digital reserve currency, instead of each country issuing its own.

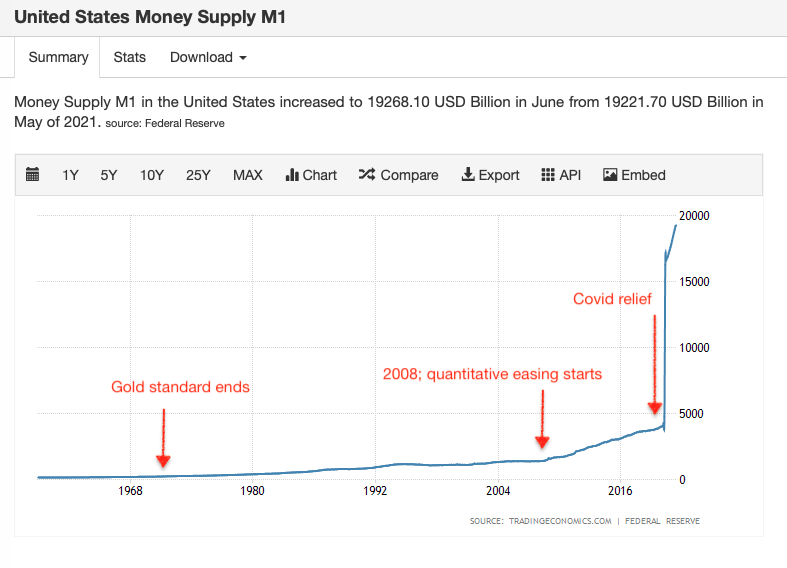

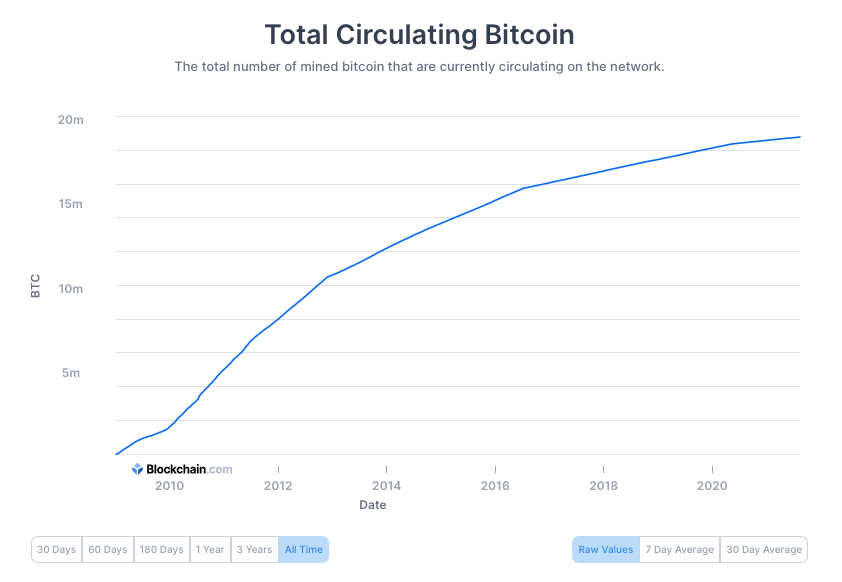

Central Bank Digital Currencies, as major economies have described them, differ significantly from cryptocurrencies like bitcoin. They are not really decentralised, because only authorised entities can run nodes on the blockchain. Tokens can only be custodied in wallets run by government-regulated entities, as with China’s e-yuan pilot. They are also likely to be backed 1:1 with actual currency (whose supply is controlled by the very central bank that issues the Digital Currency).

This is unlike even asset-backed private stablecoins like USDC, which have to either over-collateralise reserves or maintain a mix of cash and short-term deposits.

Even so, they do have potential to improve upon the digital nature of most currencies today:

One of the biggest issues with payments today is settlement. Movement of information is instantaneous, movement of money takes days. When I pay my mobile phone bill online via my debit card, the payment gateway tells Airtel (my cellphone carrier) to mark my account as paid right away, but the actual movement from my bank to the payment gateway’s central account to the carrier’s account takes about three days, delayed by weekends and bank holidays and subject to daily ‘cutoff’ times. With digital tokens, information and money can be made part of the same payload. If I were to pay the same bill with my CBDC wallet, the payment gateway could debit tokens from the wallet, mark them with my mobile number, and credit it to Airtel’s account instantly. Airtel now has both the money and the customer ID because now money not only moves instantly but carries information with it.

This was so powerful a concept that back in 2015 Goldman Sachs applied for, and in 2017 received, a patent on such a use case, which it termed setlcoin.

It was also what the company Ripple had attempted to do with cross-border transactions. Its XRP token was meant to obviate the need for nostro accounts, with foreign currency kept idle in overseas branches of banks across the world to settle payments made in one currency into the other. (Unfortunately for Ripple, the USA SEC charged the company with an ‘unregistered securities sale’, alleging that its sale of XRP to retail investors violated regulations.).

Settlement is an elementary example of the basic characteristic of a currency based on digital tokens – its programmability. Blockchains can host and execute code that manipulates tokens between wallets based on data that is either on the blockchain itself, or fetched from some other real-world source. The Ethereum blockchain, which was built for such programmability, terms these smart contracts. About a year ago, I wrote a blog post, split into four parts, on what programmable money could do, including collating several examples from other articles: (Part one, two, three, four).

One aspect of programmable money is of course giving banks and governments more fine-grained control over what capabilities money itself has. Instead of placing limitations on the account, it could do that to the very cash held in that account. If the government wanted to freeze funds for an individual, it could simply invalidate all tokens that, according to the blockchain, were currently held by the individual, regardless of what wallet or bank account they were in. Transactions on the bitcoin and other blockchains are already traceable, but are essentially anonymous. When they are tied to national IDs or other identifiers, they are much more easily trackable because an authority needn’t subpoena multiple banks and financial institutions – it could simply travel along its own blockchain.

There are positive use cases for programmable CBDCs as well. Governments can nudge responsible use of subsidies or stimulus money by whitelisting what it could be used for. The Indian e-RUPI, a form of electronic vouchers, is money tied to specific ‘merchants’ that it can be spent at. With a CBDC, that can be built into money itself (the industry jargon is ‘colouring money’). Another example of this is the one from China at the beginning of this email.

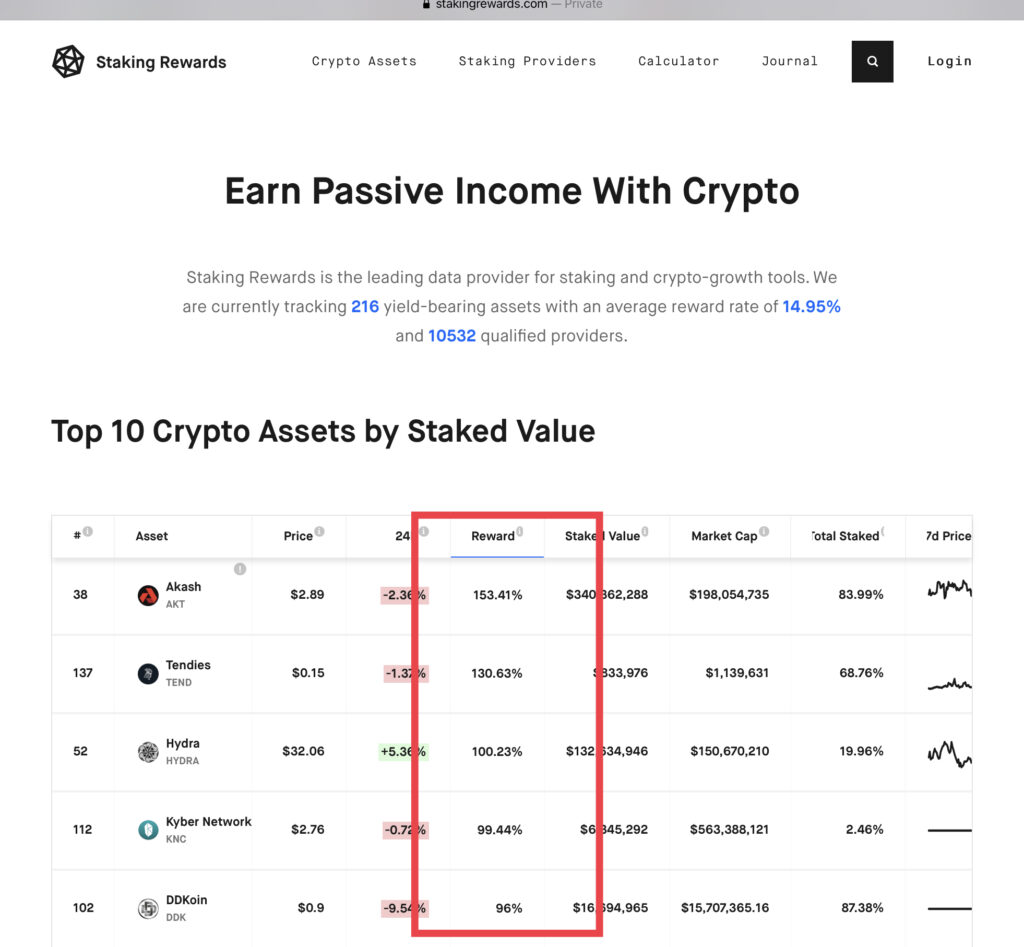

By building interest into tokenised money, CBDCs wallets can earn differential interest depending on what the money is used for, rather than what account it lies in. For example – to use Indian banking terms – money in a savings bank account earns minimal interest; locked up in a fixed deposit it earns slightly more; moved into a liquid fund somewhat more. But these are completely separate from what the deposits are used for. In an alternate future, banks – and governments – could display actual projects (infrastructure, social, environmental, commercial) or baskets of projects with interest rates that each of these pay out. This is somewhat like staking tokens in the DeFi space, and could dramatically simplify the complicated and opaque process of many types of bond issuances today by cutting away middlemen institutions.

Banks and financial institutions can also encourage responsible financial behaviour by, for instance, getting customers’ consent and tagging a fraction of their deposits as their Emergency Fund. Today banks can implement this in their internet banking software too, but it’s a software layer on top of money, as opposed to being built into cash itself. If the Emergency Fund smart contract was implemented across banks, a customer could transfer money from one bank to another and still have it marked as emergency in the other account.

In the same way today a physical wallet has notes of different denominations, a digital wallet will likely have tokens of different capabilities.

There are other programmable use cases for businesses, including multi-signature contracts that could establish joint ownership of money tokens, that require the consent of more than one party to be spent. This could obviate the need for cash to be locked up in escrow accounts.

There are implications for tax collection. When the context of every movement of money is known, smart contracts can deduct tax in transit. At its extreme, tax collection could be baked into the flow of economy, no longer the responsibility of individuals or businesses, who could claim credit for tax breaks post-facto every quarter or year. The savings in time could be tremendous.

In any case, central banks, through governments, are likely to aggressively preserve their monopoly on digital currencies. Facebook’s announcement of their quasi-digital-currency Libra in 2019 met with immediate resistance from the USA government, with senators discouraging the CEOs of Visa, Mastercard and other major initial participants from associating themselves with the project. The text of the letter is noteworthy for the level of alarm and the breadth of its attack on Facebook. Facebook has since launched Diem, a re-branded digital currency, seeking Swiss jurisdiction. More recently, the USA SEC chairman Gensler, made it clear in a public speech just last month in July that he intended to seek regulation of all sorts of stablecoins, whether backed directly by cash, or structured as derivative contracts.

In sum, I think CBDCs aren’t cryptocurrencies and they aren’t ‘stablecoins’. But they are – potentially – dramatically different from today’s digitised fiat currency. Issuing money as tokens on a blockchain (however centralised that blockchain may be) creates programmable money, reusing primitives, practices and technology from the DeFI space.

Many of the use cases above never be implemented. Some of them may take years to come to pass. Digital literacy, and financial literacy are perhaps the biggest challenge of all.

But the model, to me, seems to be inevitable. And something I cautiously look forward to.

(ends)

📪 To get these posts delivered as email, sign up to the On Crypto, Bitcoin and DeFi newsletter on Substack now.